This is a review of a video titled “The Colourful Mr. Eggleston”, part of the BBC’s Imagine series (see full reference below).

Over the years I’ve seen a lot of the work of William Eggleston. I have to admit that I just didn’t get it. Apart from an historic and popular culture perspective, I didn’t understand what all the fuss was about. This video started to change my mind. The door opened (just a little) to understanding that maybe there is more than meets the eye.

Background

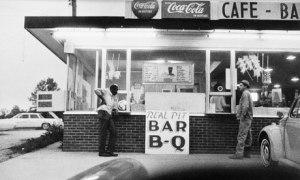

According to Wikipedia, William Eggleston was born in 1939 in Memphis, Tennessee and raised in Sumner, Mississippi. According to the video, he got his first camera at the age of 18 and started with black and white, teaching himself. Even in those days, his photos were of everyday scenes and have a lot in common with his later colour work.

Life, Today

After a brief introduction the presenter sets the scene succinctly by stating that “his subject matter is the banal, the everyday” and this label is almost echoed later by Eggleston himself when he says that people often ask what he photographs. He says that his best response is “life, today”. This seems like a good enough working title for what he does. At least on the surface.

It’s interesting to see in the video his method of working – he raises his camera quickly to his eye and “click” – it’s done. Apparently he is well known for this way of working and even mentions it himself: “I do have a personal discipline of only taking one picture of one thing, not two.” He puts this in perspective by saying that in the past he would have trouble choosing the best if he took more than one frame.

At one point Eggleston opens the famous Henri Cartier-Besson book, Une Décisive Moment1and remarks that “… this is not just photojournalism, this is great art”. He points out Cartier-Bresson’s use of composition and obvious knowledge of painting and states that there is a lot of Dégas and other painters in his photos.

In the mid 1960’s he switched to using colour film. Martin Parr points out that the switch was actually quite radical at the time because in those days “to be a serious photographer, you had to be working in black and white”. He goes on to say that it took a long time to appreciate the “underplayed” nature of Eggleston’s work – even though it was in colour, it was a “nothingness colour”. Eggleston took the process on step further, however by using the relatively expensive dye transfer printing process due to its “incredible saturation and colours which never fade”. At the time, the printing process was used for fashion and marketing materials, but not for art photography.

At 09:40 Rosa Eggleston (his wife) recalls how William warned her against taking anything for granted – “every single, little, tiny space on that page works and counts.” This is significant because it gives us a hint about how to go beyond the surface of Eggleston’s images and see the full picture. Using this as a starting point and reviewing his photos, it quickly becomes clear about what he meant: that each component of the photo is there for a reason – there is little which is extraneous. In the three photos below, it is possible to see even conventional ideas of composition using leading lines and balancing objects across the frame.

At 08:43, Mark Holborn comments on the “inherit geometry” and fluidity of the photos of Henri Cartier-Bresson. He also says that he thinks “that’s what Eggleston aspired to.”

|

|

|

Martin Parr comments later that:

The composition appears so intuitive, so natural, it’s not forced upon us at all. It appears the simplest thing, but of course when you analyse it, it becomes actually quite sophisticated and messages that these pictures can release to us are quite complex and fascinating. Of course, it’s the hallmark of a very good Eggleston.

At 12:28, Rosa Eggleston recalls an occasion William when asked his “great, highly respected friend” (without saying who this friend was) what he should photograph because everything around him was so “ugly”. The friend replied that he should “photograph the ugly stuff.” According to Rosa, that is how he started – photographing the explosion of shopping centres and other such “ugly stuff” around his home area.

This comment is interesting because it is one thing for a friend to suggest subject matter and quite another for us, as photographers, to be open-minded enough to be interested in the suggestion. At that time, the suggestion must have appeared very radical but perhaps also attractive because because it would have been in-line with his disinterest with so-called “art photography” i.e. Ansel Adams, Edward Weston.

In an interview with the Whitney Museum (2009), Eggleston said that he “wanted to see a lot of things in colour because the world is in colour”. Beyond this point, it is plain that the quality of light is also very important: many photos were taken either early morning or late afternoon with glancing sun. In the same interview he went on to say he “was affected by it [colour] all the time, particularly certain times of the day when the sun made things really starkly stand out.” I think that it’s hard for us to imagine what it must have been like back then – to break the rules on two counts: not only to use colour for art photography, but to photograph nothing at all!

At around the 47:44 point in the video, Martin Parr says that the first thing that he looks for in a photographer’s work is a sense of vision but points out that in photography it is one of the hardest things to achieve. He goes on to say that “Eggleston is a photographer’s photographer because the vision is almost undescribable … because it’s about photographing democratically and photographing nothing and making it interesting, and that would seem to me to be the most difficult thing to achieve of all.”

Conclusions

The work of Eggleston is sometimes suggested to OCA students as background for the Square Mile assignment. When looking at his full body of work, I developed a feel for what William Eggleston’s square mile must have been like in the 50s and 60s. I imagine that it might be possible to select 6-10 photos (as required by the assignment) which are sufficiently representative to work as a set and also to communicate sufficiently what his square mile was like. But would that set necessarily be about his square mile or would it instead be about him? The more I look into his photography, the less simple I think it is to separate William Eggleston the person from his photographs. To put it in another way: if he was put into another locality, would he make another set of photographs which describe that locality or would the photographs describe William Eggleston?

Robert Adams, as quoted by Alexander (2014) suggests that there are three varieties of landscape pictures: geography, autobiography and metaphor. There is nothing much to say from a geographical perspective – the photos are “perfectly banal”, to quote the New York Times commentary on Eggleston’s first exhibition at the MOMA.

From an autobiographical point of view, there is more to say. Many of the earlier images have curiosity or historic value. They show people who are dressed differently to today, who have hairstyles which are strongly associated with the period and drive cars with distinct styling from the period. For people who remember this time, there must be a strong feeling of nostalgia. Of course the content also works in another autobiographical sense because of the advice from the “great, highly respected friend”. Imagine what would have happened if this friend had told Eggleston to “go shoot weddings”?

The metaphor aspect is interesting. At 21:50, Peter Fraser talks about a “very disconcerting feeling of dark forces” in a family home. Eggleston’s photos of people are not “happy snaps”. In most cases, the expressions are serious, even threatening, making us wonder about what is happening and why. There is often a sense of isolation and loneliness, which (again, autobiography) possibly relates to Eggleston’s own childhood.

After watching this video several times and reading and watching associated articles and videos, I came to the conclusion that there is something profoundly interesting in Eggleston’s work which gets under one’s skin. Finally, I agree with the presenter: the tag line “perfectly banal” is actually the point. It fits – beautifully.

References

Alexander, Jesse (2014) Perspectives on Place: Theory and Practice in Landscape Photography [Kindle Edition] From: Amazon.com (Accessed on 29.09.15)

Imagine | The Colourful Mr. Eggleston Pres. Yentob. BBC UK (2013) 48 min At: http://shutyouraperture.com/the-colourful-mr-eggleston/ (Accessed 11-Jan-2016)

Wikipedia. William Eggleston. At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Eggleston (Accessed 11-Jan-2016)

William Eggleston at the Whitney Museum of American Art Whitney Museum (2009) At: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j0D97U2RlNU&list=PL1E60C5F434CC369B (Accessed 12-Jan-2016)

Notes

- Oddly, this looks like incorrect French – moment is a singular, masculine noun, therefore it should be “Un Moment Décisif”, but obviously there must be something more to it.

Pingback: Saul Leiter: Early Color | Darryl's Context & Narrative Blog